Wine and Millennial Silence

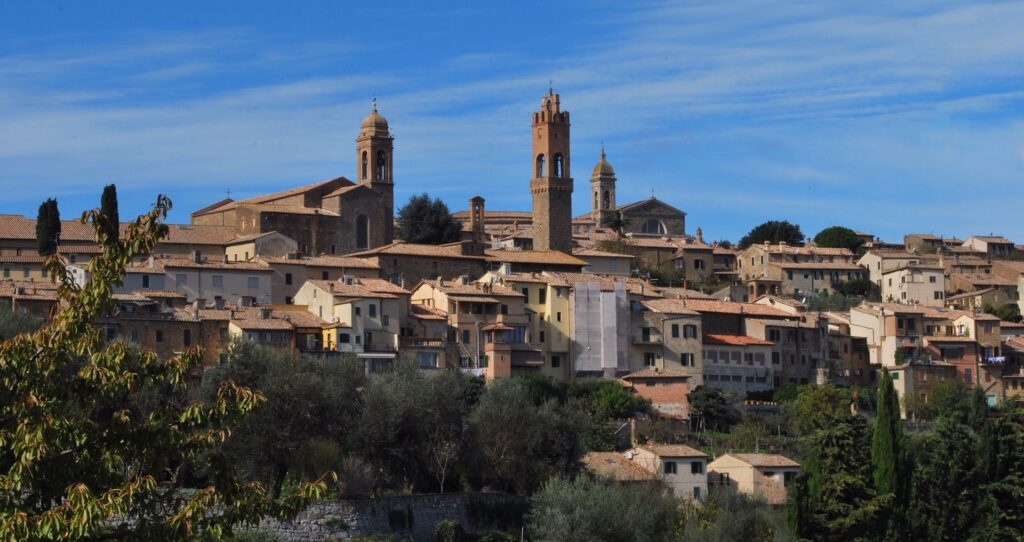

Like many towns in the region, Montalcino was founded by the Etruscans and flourished between the 13th and 16th centuries thanks to its strategic hilltop position. For centuries it was caught between the rival ambitions of Florence and Siena. In 1361, after the Sienese captured it from Florence, they built the imposing pentagonal fortress that still dominates the town. Montalcino’s loyalty to Siena was so strong that, after Florence defeated Siena in 1555, it sheltered 700 exiles and even became the seat of the “Republic of Siena in Montalcino” until 1559. This proud independence is remembered today when Montalcino’s banner joins the parade at Siena’s Palio.

Beyond its fortress walls, Montalcino’s true fame rests on Brunello di Montalcino. As early as the 15th century the town was known for fine red wines, but the modern Brunello was created in 1888 by Ferruccio Biondi-Santi, who broke with Chianti tradition by vinifying only the Sangiovese grape (locally called Sangiovese Grosso; the word Brunello—“little dark one”—was once a nickname for this grape). His innovation produced a deep, structured wine capable of extraordinary aging. It would take nearly a century, however, before Brunello gained international prestige. In the 1970s, the Italian-American Mariani family founded Castello Banfi and introduced Brunello to the United States, combining modern marketing with centuries of Tuscan winemaking know-how. Today Brunello ranks among the most prestigious wines of Italy—and the world.

Montalcino also celebrates its wine through world-class events. Every July, the Jazz & Wine Festival fills the fortress and vineyards with international jazz concerts paired with Brunello tastings. And each winter, Benvenuto Brunello presents the newest vintage to critics and enthusiasts from around the globe, reinforcing the town’s reputation as a capital of fine wine.

Just beyond the town, the Abbey of Sant’Antimo adds another layer of timelessness: a Romanesque jewel said to have been founded by Charlemagne in 781. Its pale travertine stones glow golden at sunset, while inside, silence is broken only by the echo of Gregorian chant—a reminder that here, history, spirituality, and nature remain deeply intertwined.